The relationship between animals and physiotherapy is not a widely explored arena, though one that should get significantly more attention in light of today’s environmental crises. Truth is, I am completely out of my depth here, but I am nonetheless going to jump in head first because I think it is such an interesting and, actually, important area that it at least needs to be mentioned sooner rather than later as imagine what an environmental physiotherapy might be. Hopefully we can have some people with more expertise in this field publish some blogposts for us in the future that will do it more justice.

Physiotherapy has had a relation to animals for a number of years now. Animal physiotherapy, ie. physiotherapy for animals is generally considered to have been brought to life by Sir Charles Strong, a physiotherapist who developed an interest in this field following an interaction with a client of his who was also an eager polo-player, and subsequently published the first book on physical therapy for horses in 1967 (Catalayud, 2019). Since then, animal physiotherapy has grown quite considerably. The International Association of Physical Therapists in Animal Practice (IAPTAP) was officially recognised as a subgroup of the WCPT in 2011. In 2014, The Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Animal Therapy (ACPAT), a special interest group of UK’s Chartered Society of Physiotherapists (CSP) already had as much as 300 practitioner members (Price, 2014), while at the same time, the Working Group of Physiotherapy in Animals of the Spanish General Council of the Official Colleges of Physiotherapist (CGCFE) began its work for the promotion, development and defense of this speciality, following the creation of a first working group in 2002‘ (Catalayud, 2019).

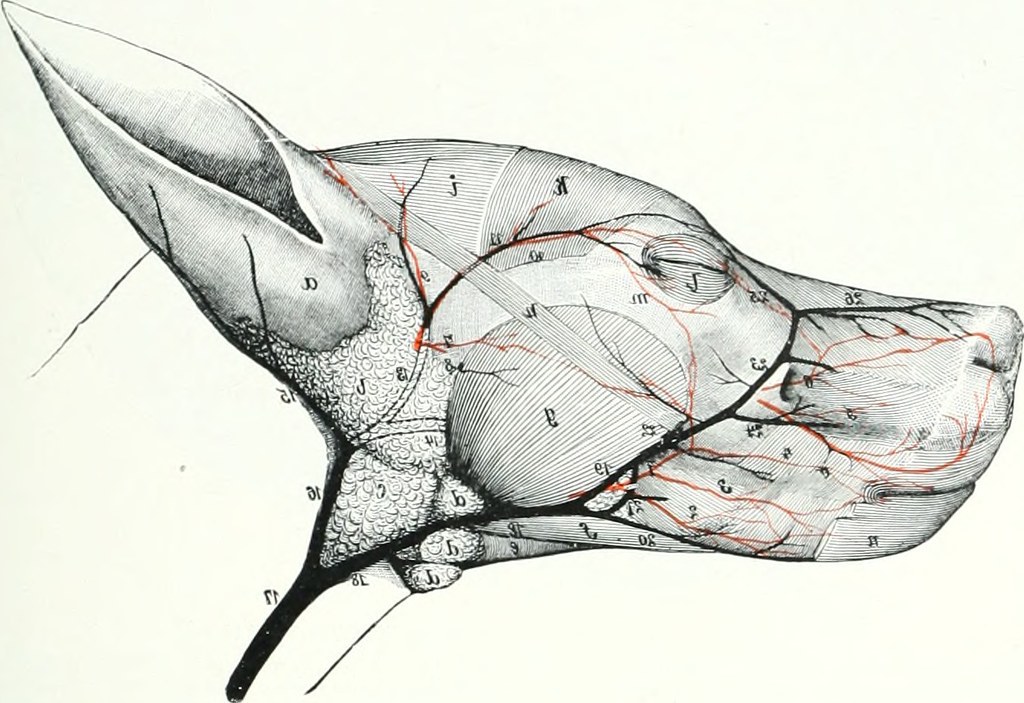

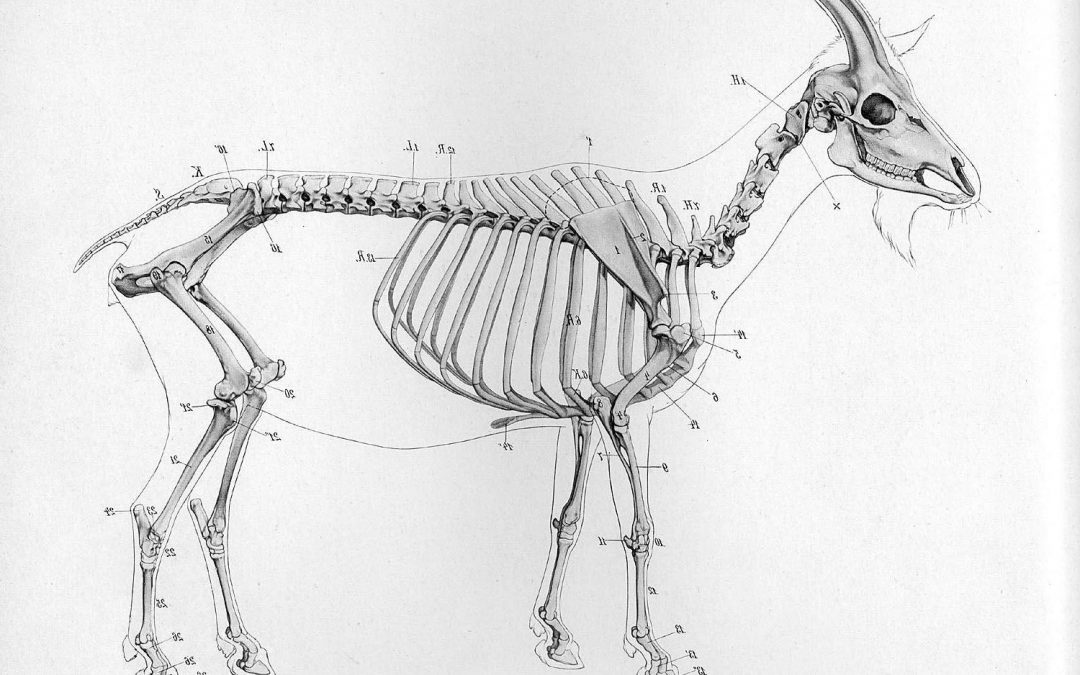

There are also a number of specialised educational programmes available in the UK and around the world, and by now, animal (or, veterinary) physiotherapy is not only provided to horses, but also dogs, cats, and other small animals, including apparently even turtles. The research base underpinning animal physiotherapy is also steadily growing, so in a very superficial and quick search I’ve been able to find quite a large number of recent articles, particularly from the 1990’s and then the 2000’s onwards, which I presume might correspond to the increasing settling in of physiotherapy into academia and academic research. There are also full-length books in the subject field, like e.g. Animal Physiotherapy: Assessment, Treatment and rehabilitation of Animals (2nd edition) and a good amount of very recent research in the field.

Another not so small field that is at least fairly close to physiotherapy are animal prosthetics. Check out this google image search for ‘animal prosthethics’ and your heart will melt as you can see the most amazing contraptions created for anything from dogs, through horses and miniature horses and even, birds, mice, goats, and even cangaroos and elephants being helped by the use of prosthetics. I won’t go into it much here, but it definitely needs to be included into any thinking concerned with the relationship between physiotherapy and animals.

Despite all there is in and around animal physiotherapy, I would argue that it still has a kind of shadow existence in our profession, and in a broader sense, animals are completely marginalised, if not shunned. One of the things that I find interesting about this, is that it is by no means specific to physiotherapy, but a general sign of our times and one of the key components of the environmental crises we are facing today. Much like insects are not only dying out in staggering numbers, but even disappearing from textbooks, in the context of physiotherapy, animals seem to have never even made it into the textbooks or undergraduate curricula, but are pushed outside into ‘special’ interest groups and training programs.

Another interesting element here might be that animal physiotherapy, at least from what I gather so far, seems to be built on the idea that it is an extension, or further development of human physiotherapy applied to animals. Gowan, Stubbs, and Jull (2007), for example, argued that equine physiotherapy ‘should be guided by the most recent advances in the human field’ and look to focus on ’employing and improving existing research techniques using a human physiotherapy model’. This is possibly not emblematic for animal physiotherapy, or probably doesn’t do justice to all of its aspects, but it is nonetheless interesting to note, and there are definitely other pointers towards animal physiotherapy often being thought of as ‘human physiotherapy techniques to manage similar problems in veterinary patients’ (Veenmann, 2006).

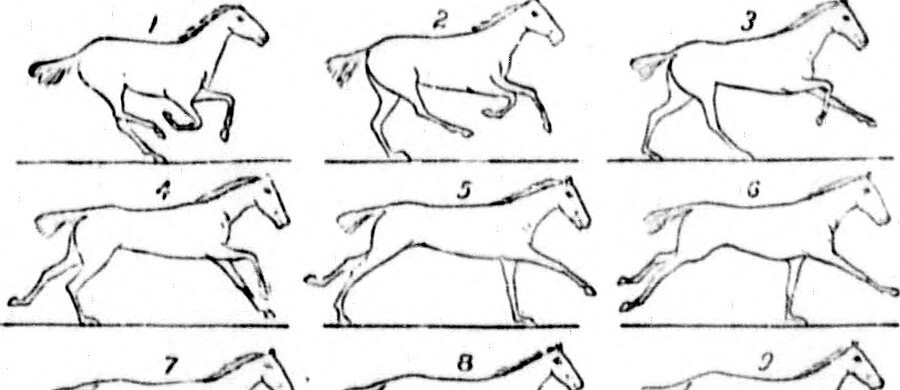

This, however, raises a number of very interesting issues. First of all, the human model that Gowan et al. seem to talk about is very biomedical, given that it should focus on ‘neuromotor control… stability… the sensorimotor system… locomotion and biomechanics’ and ‘functional biomechanics’. But if these are being questioned in human healthcare and physiotherapy (be it via the BPS model or more critical physiotherapy approaches), then why would we extend it to animals?

Next, if we were to extend the BPS model to animals, then we would still have to find out if this transfer is accurate, and even just, or if it is a somehow questionable anthropomorphisation. Thankfully we are fairly clear by now that animals do think and feel, and even feel pain. But I’m not sure if we are sufficiently sure about them doing it in the same way that we do, and whether this warrants a direct transposition of a human health model onto animals.

That said, I’m inclined to think there is some relationship here and maybe the more important point is that physiotherapists are largely still blissfully, professionally unaware of the fact that animals get sick, think and feel joy and pain, and have therefore also not thought about whether this doesn’t warrant them also being provided with (health)care and even physiotherapy.

Another interesting element in the human / animal physiotherapy model and the relegation of animal physiotherapy into the profession’s margins is that it still shows for us considering animals as separate from humans. Next to many other such distinctions like e.g. that of culture and nature, this is a highly contested perspective in current philosophy revolving around questions of the posthuman (I’ll refrain from linking specific references here and let you open that pandora’s box yourself).

To summarise in some manner, I have recently had the pleasure of attending a talk by Hélène Mialet, a philosopher and anthropologist of science and technology who presented on an ethnographic study she conducted at a facility training dogs to recognise hypoglycemic episodes in people with Type 1 Diabetes. Her work in this area powerfully supports the key argument that the distinction we make between humans, animals, and even machines cannot be upheld as rigidly any longer. In other words, the human ‘doesn’t stop at the boundary of the flesh’ but is entangled with animals, ecosystems, and even technology to an incredibly deep and virtually inseparable degree. In other words, we are always already entangled with other species that live around, among, with and even inside of us (another good read here). And so the point of this in regard to healthcare and physiotherapy is that it really makes no sense to think about and practice physiotherapy in a manner that keeps them separate, one program here, and another there.

Thankfully, it is increasingly acknowledged that human and animal health are inseparably related in a number of ways. We are increasingly aware that the loss of biodiversity is not just an environmental emergency, but also a health emergency, much like the climate crisis, and these are, in fact, inseparably related to each other (some reading here and here). If you ever have any doubts with regard to the importance of animals to human health and survival, try eating anything without an animal having been involved in some part of the chain leading to the production of what you are putting into your mouth. It should be obvious this is not going to happen (disregarding possible lab based developments). So animals clearly contribute to human health and survival as food and as aids in the production of food (as pollinators, as soil-carers, or else).

The seemingly simple point being made here, across e.g. planetary health and One Health, is that caring for animals is also caring for humans (health) and it’s really not sensible to separate them. Extra incentives for caring for animals as a measure for human health might be found in the fact that animals also contribute to carbon-sequestration and are actually important allies in addressing climate change. Look at it whichever way you will, symbiosis is a thing and you really can’t think or ensure human health and functioning without also thinking about animals (and then some).

A final field that should be mentioned in discussing the relation between human health, physiotherapy and animals, is animal assisted therapy. I will just point you to some interesting reading here, here, and here and say that the general tenor is that animal assisted therapy also contributes to mental wellbeing, reductions in the perception of pain, pain induced insomnia, intervention adherence and patient satisfaction. So how is this not directly relevant to physiotherapy?

Again, there are some physiotherapists that work in this field, but I am not sure how deliberately ‘animal assisted physiotherapy’ is linked to ‘animal physiotherapy’, or if it is just treated as yet another separate field, and maybe more importantly, if we have truly explored this field enough. I would like to think that there is more that could be done here. And to finally end this post, I suppose my key point is this:

Just as much as physiotherapy cannot be thought of without thinking about the environmental, it cannot be thought of without acknowledging that animals are always already also at the centre of this equation.

If we are to transition towards a truly environmentally aware and responsible physiotherapy (or, sustainable healthcare, or planetary health approach, etc. for that matter) we must also consider animals, the human-animal, animal-ecosystems, and human-animal-planet relations as one of our key fields of inquiry, and likely also a key field of practice. It is high-time we stopped treating animals and animal-relations as some kind of X-files relegated to the obscure. This would also enable us to not only factor in the many ways that they do things for us and can contribute to our health, but also if we could do something more for them, and maybe even come up with some new ways of living that ‘that are less parasitic, and instead framed more by attempts at producing opportunities for mutualistic flourishing’ (Gorman, 2019). We might have some hints at this in animal physiotherapy and animal-assisted physiotherapy already, so why not explore them further.

Filip Maric (PhD)

Filip Maric is a physiotherapist and researcher interested in practical philosophy, ethics, environmental physiotherapy, planetary health and sea kayaking.

Hello Filip

Thanks for citing my article.

I would be happy to contact the association and offer some kind of colaboration.

Kind Regards

Dear Maria, I would love that and will contact you via email right away. Best regards, Filip

Hi Filip, thank you for a well-written article. I am an veterinary/animal physiotherapist, and I would like to politely challenge your suggestion that animal physios may work only within a biomedical-type model, in dealing with our animal patients.

I cannot speak for all avenues of training, but certainly in my post-graduate degree, in all the (specifically, physiotherapy-led) courses I’ve since attended, and in my clinical practice, the psychological and social aspects of addressing a problem, strongly feature. I can understand why this might not come across clearly, based on the majority of what is currently published, but many of these texts are not aimed at physios, to inform and improve their holistic, BPS-orientated practice. They are just reference books, more likely aimed at vets, to help inform them of the scope of our knowledge and skills. Many vets still think that we just do a nice back massage! And whilst my human physio background strongly influences and informs my animal work (and CSU has built a new centre that will specifically look at how human rehabilitation can influence and advance the Veterinary field), good animal physios also recognise what is different about animals, how they organise their movement, how movement and behaviour is inextricably linked, and how their physical, social, and psychological environments and routines are affected. The dog who becomes depressed because it is on crate-rest and is not allowed to go on walks with its humans to the local cafe, the horse who develops a fear of saddles due to chronic pain…these are easy examples of things we encounter in practice. I would be very happy to discuss this with you in more detail, if you’re interested.

And in terms of animal health and the connection to human health…beautifully put. You may be interested in speaking to a veterinarian colleague and friend of mine, who is a champion of their exact concept. I’d be happy to put you in contact with her.

Many thanks again, and best regards

Helen

Dear Helen,

thank you so much for reading the article and your comments.

I actually love everything that you are saying here and would love the opportunity to talk to you and your colleague more about the non-biomedical aspects of animal physiotherapy, as well as how animal health can inform human health and rehabilitation, so yes please, let’s get in touch about all this. I will send you an email also just in case you miss this reply.

Looking forward to continuing this conversation.

Best regards,

Filip

Hi Filip, I haven’t seen your email yet, just re-replying to make sure that I haven’t missed it