There used to be a runway made of ice.

Every winter, when the wild Bering Sea solidified between the tiny village of Little Diomede and the military outpost at nearby Big Diomede, the United States and Russia was temporarily connected by a thick, two-mile stretch. Weather permitting, small planes from Nome would transport cargo and passengers—including visiting clinicians—as long as the ice held out.

In 2008, early in my career as a physiotherapist serving northwest Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, I traveled to Little Diomede for a two-day field visit. The week before, older, and more seasoned hospital colleagues warned me about the unpredictability of travel to and from “The Rock.” They regaled me with tales of colleagues whose stays had been extended by days—or months—and jokingly said they’d see me next summer. It was late in the season—edging into April—and an early breakup could collapse the runway. A combination of scheduling conflicts in Nome and missing keys to the bulldozer used to clear the Little Diomede airstrip had already delayed my visit.

After a day of seeing walk-in patients at the tiny clinic, the local health aide invited me for a snowmachine ride. We sped over blue-gray sea ice, past crabbing holes, between the jagged village hillside behind us and the sheer Russian cliffs ahead. The International Date Line—and the border between time zones, countries, and continents—lay invisibly between.

Over a decade later, that ice runway has receded into history. The sea ice no longer thickens sufficiently for planes to land upon it. Winter travel to and from the island includes a flight that lands in nearby Wales, then a short helicopter trip over to Little Diomede.

Monica Roe (PT, )

MPH student, University of Alaska, Anchorage

Monica Roe is an author, physical therapist, beekeeper, and researcher/advocate for the social model of disability and inclusive rural health. A first-generation graduate, Monica studies public health and disability-inclusive disaster preparedness at the University of Alaska. She and her family divide their time between Alaska and their apiary in rural South Carolina.

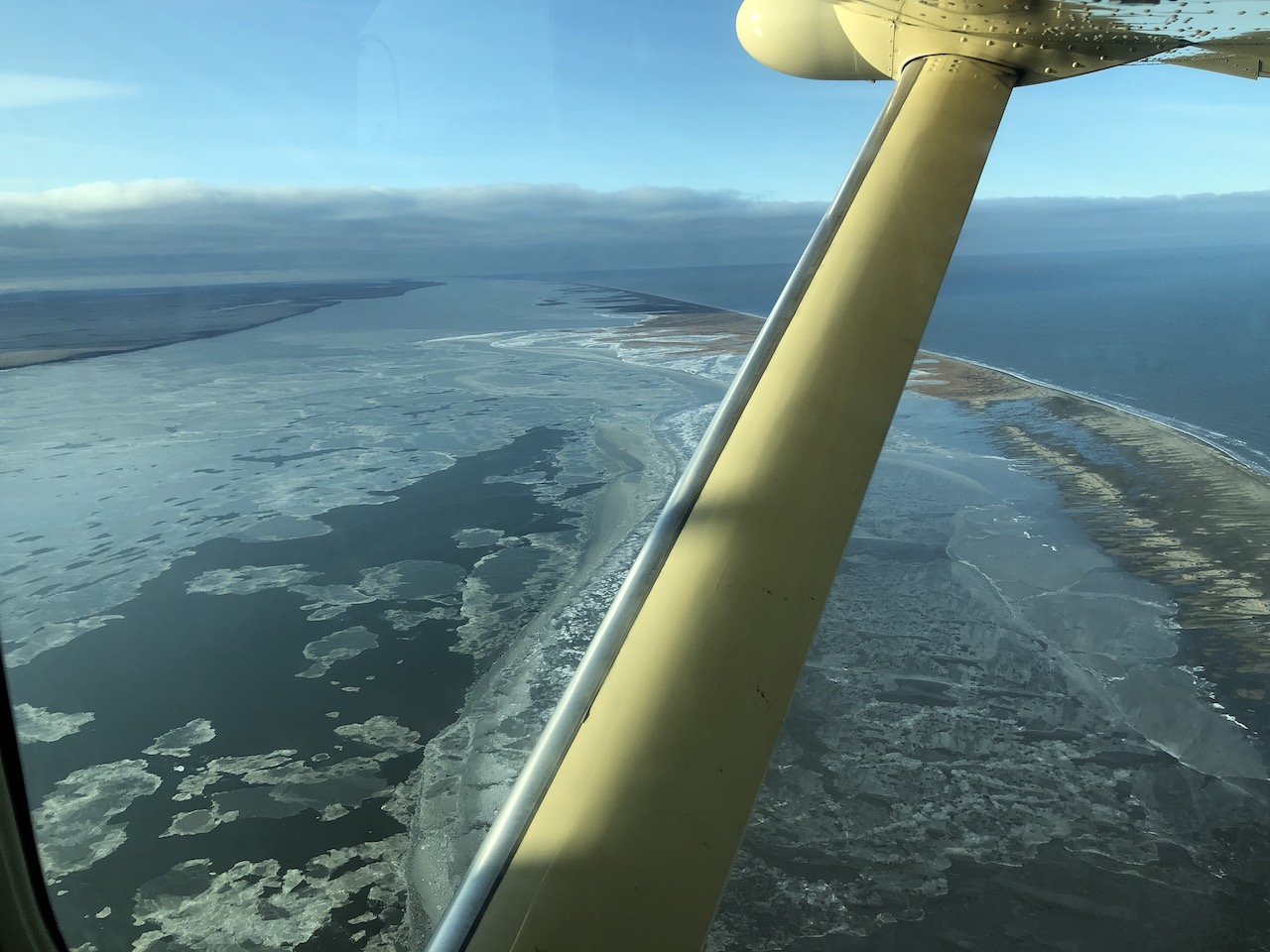

In the nearly fifteen years I’ve served this region, commuting between communities by small plane, the here-no-longer ice runway isn’t the only change I’ve witnessed. The inexorable march of climate change—accelerating worldwide—is affecting the global arctic four times faster than other regions. Gazing from the windows of hundreds of flights has provided a bird’s-eye view of dramatic, troubling shifts. Swathes of permafrost sinking as they thaw. Spring ice breakups occurring in midwinter, disrupting marine mammal migrations and traditional Indigenous hunting practices.

In my early years here, the 200-mile stretch between Nome and St. Lawrence Island froze solid for months, with initial springtime cracks slowly giving way to open water and, finally, the spring breakup. More recently, I have observed years where the middle never quite freezes completely. Year by year, degree by degree, the arctic is sounding an urgent alarm.

Paradoxically, the provision of disability-specific services has always been slower and barrier-filled here—even as climate change accelerates faster. Physiotherapy practice in the arctic—and to live with disability here—is shaped by access and equity, geography, and weather. Simple consults and follow-ups are subject to storms, aircraft mechanics, and the internet connection needed to support telehealth outreach. Obtaining mobility aids and assistive devices is routinely impacted by frustrating barriers. Justifying the need for heavy-duty tundra tires for a wheelchair by phone to a skeptical insurance provider—then trying to explain gravel substrate and the fact that the nearest sidewalk is 500 miles from a client’s home. The months-long wait for a needed piece of equipment to be air-freighted to a community—only to arrive irreparably damaged in transit.

These struggles, nothing new, are increasing in complexity as climate change crescendos around us. Rough weather and rough travel are accepted facts of life. But warming temperatures are spawning larger, wilder storms, threatening low-lying coastal communities. In 2013, I spent six days weathered in Newtok, a community on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, as brutal crosswinds buffeted the village and grounded flights. Since then, coastal erosion and rising seas have forced the community to relocate inland—and other communities face similar threats.

In 2016, an earthquake off the Japanese coast triggered tsunami warnings, grounding flights throughout Alaska. I was in Gambell—a community on St. Lawrence Island exactly zero feet above sea level. As we watched the sea and waited for updates, I thought about how citizens with disabilities in already-vulnerable communities are doubly impacted when emergency events loom. The tsunami didn’t materialize and we didn’t have to activate the evacuation plan (running up a slippery, gravel-covered ridge nearby if the village became inundated). The warning was lifted, planes began flying, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. But the seas still warm and the weather worsens. In September 2022, I was again traveling through the region when ex-Typhoon Merbok, fueled partially by warmer-than-usual water, formed over the Pacific, churned eastward, and took aim at Western Alaska. It would later go on record as the strongest storm to occur in the region so early in the fall. Storm surges breached seawalls, homes floated off foundations, whole communities sheltered in schools, and protective berms were washed away.

The Seward Peninsula is a resilient place, rooted in community and interconnectedness. But even with a supportive community framework, those with disabilities are increasingly vulnerable as communities grow ever-more subject to extreme weather events. As the arctic moves forward into an unknown future, disability-inclusive disaster planning, accessible shelter and evacuation, and shared decision-making are needed to mitigate equity and access issues that risk worsening existing disparities.

Fifteen years of watching the landscape shift, ice thin, waters rise, and communities plan for the worst has fundamentally shifted how I envision the intersection of disability, geography, and justice in an ever-warming, ever-wilding world. I believe physiotherapists can—and must—shoulder responsibility far beyond the provision of physical rehabilitation. By partnering with the disability community, promoting community-based participatory research, and lending our expertise to inclusive disaster planning and policy innovations, we may be uniquely positioned to help center and amplify the voices and needs of those we serve.

Ice runways collapse, seas warm, and tides surge. But the human spirit, ever-resilient and ever-creative, can meet these challenges if we come together to radically re-imagine the boundaries of the possible.

Very well written and very informative. Thanks for sharing.