Ageing is a natural part of life, but how we manage this phase can vary significantly depending on where we live. “Ageing in place” is a global strategy aimed at supporting older people to remain living in their own homes while maintaining connections with social networks and daily activities (1). Although this ageing strategy is often described as supporting people in maintaining social connections, meaningfulness, and a sense of identity, health and social care services often tend to overlook outdoor participation for older people, as activities inside the house are often prioritized (2, 3). Ageing in place in rural Arctic contexts, where geographical and climatical challenges may be significant, is particularly underexplored (4).

Challenges in rural Arctic Norway

What ageing in place means in rural Arctic environments is not very well defined. In such contexts, older people may face unique challenges such as long, dark winters, snowy and slippery surfaces, and vast distances between facilities (5). In addition to enhanced social participation (6), reduced loneliness (7), and improved mental and physical health (8), engagement in nature and outdoor places can provide a sense of meaning and belonging. Particularly, people living in the rural Arctic have lived in close contact with nature (9, 10). Therefore, understanding cultural attachment to places is crucial for achieving meaningful and healthy ageing in these areas. However, implementing new strategies in health and care services presents significant challenges and often fails because of poor contextual adaptations (11). Therefore, contextual adaptations that consider environmental factors are necessary when planning for new strategies.

A socio-ecological model for supporting outdoor engagement in rural Arctic contexts

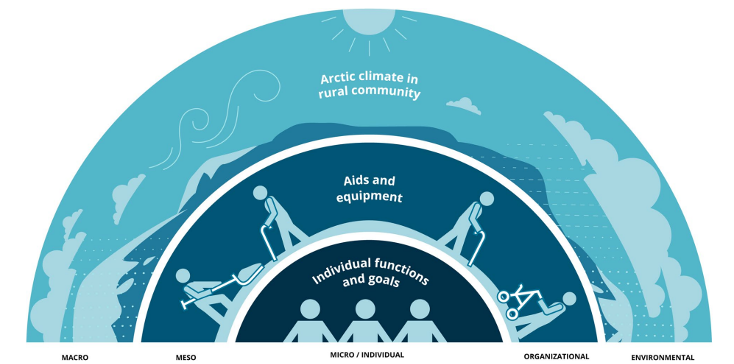

To address these challenges when aiming for ageing in outdoor places, we suggest a socioecological model focused on integrating outdoor activities as part of health and care services for older people. The model operates on three levels:

Individual Level: Adapting to the unique needs and resources of the individual.

Organizational Level: Creating an organizational infrastructure that supports ageing in place.

Environmental Level: Adapting to the rural Arctic environment, including cultural, geographical, and climatic conditions.

Marianne Eliassen (PT, PhD)

Associate Professor

Marianne Eliassen is Associate Professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. and Head of the Master’s degree program in Health Professional Development. Her research interests include health services research, often with a focus on the Arctic contexts and their particular social and environmental challenges.

Figure: A socio ecological model to support Ageing in place in a rural Arctic context.

Such a model secures sensitivity to individual, organizational and environmental factors at the same time. It recognizes the significant role outdoor places play in the lives of people and seeks to leverage this relationship for aging in place, within an interpretation of Aging in place as something more than living as long as possible in one’s own house.

The way forward

Aging in place in rural Arctic presents both challenges and opportunities. To ensure that older people in rural Arctic communities have the same opportunities as those in urban areas, a multisectoral approach is necessary. This involves developing services that focus not only on individual needs but also on the physical, social, and cultural environments where people reside. By doing so, we can help reduce social inequalities and support meaningful ageing for older people in these unique areas.

Read the full article here

Eliassen, M., Hartviksen, T. A., Holm, S., Sørensen, B. A., & Zingmark, M. (2024). Aging in (a meaningful) place – appropriateness and feasibility of Outdoor Reablement in a rural Arctic setting. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-12031-7

References

Header image by Vidar Nordli-Mathisen on Unsplash

(1) Lewis C, Buffel T. Aging in place and the places of aging: A longitudinal study. Journal of aging studies. 2020;54:100870.

(2) Zingmark M, Evertsson B, Haak M. Characteristics of occupational therapy and physiotherapy within the context of reablement in Swedish municipalities: A national survey. Health & social care in the community. 2020;28(3):1010-9.

(3) Doh D, Smith R, Gevers P. Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Ageing & Society. 2020;40(6):1371-83.

(4) Montayre J, Foster J, Zhao IY, Kong A, Leung AY, Molassiotis A, et al. Age‐friendly interventions in rural and remote areas: A scoping review. Australasian journal on ageing. 2022;41(4):490-500.

(5) Eliassen M, Hartviksen TA, Holm S, Sørensen BA, Zingmark M. Aging in (a meaningful) place–appropriateness and feasibility of Outdoor Reablement in a rural Arctic setting. BMC Health Services Research. 2024;24(1):1-16.

(6) Sánchez-González D, Egea-Jiménez C. Outdoor Green Spaces and Active Ageing from the Perspective of Environmental Gerontology. In: Rojo-Pérez F, Fernández-Mayoralas G, editors. Handbook of Active Ageing and Quality of Life: From Concepts to Applications. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 235-51.

(7) Astell-Burt T, Hartig T, Putra IGNE, Walsan R, Dendup T, Feng X. Green space and loneliness: A systematic review with theoretical and methodological guidance for future research. Science of the total environment. 2022;847:157521.

(8) Nguyen P-Y, Astell-Burt T, Rahimi-Ardabili H, Feng X. Effect of nature prescriptions on cardiometabolic and mental health, and physical activity: a systematic review. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2023;7(4):e313-e28.

(9) Kaltenborn BP, Linnell JD, Baggethun EG, Lindhjem H, Thomassen J, Chan KM. Ecosystem services and cultural values as building blocks for ‘the good life’. A case study in the community of Røst, Lofoten Islands, Norway. Ecological economics. 2017;140:166-76.

(10) Eliassen M, Sørensen BA, Hartviksen TA, Holm S, Zingmark M. Emplacing reablement co-creating an outdoor recreation model in the rural Arctic. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2023;82(1):2273013.

(11) Trinkley KE, Glasgow RE, D’Mello S, Fort MP, Ford B, Rabin BA. The iPRISM webtool: an interactive tool to pragmatically guide the iterative use of the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model in public health and clinical settings. Implementation Science Communications. 2023;4(1):116.

Excellent well meaning contribution. Without disturbing the natural ecological system plans can be executed for active engagements and social inclusions.