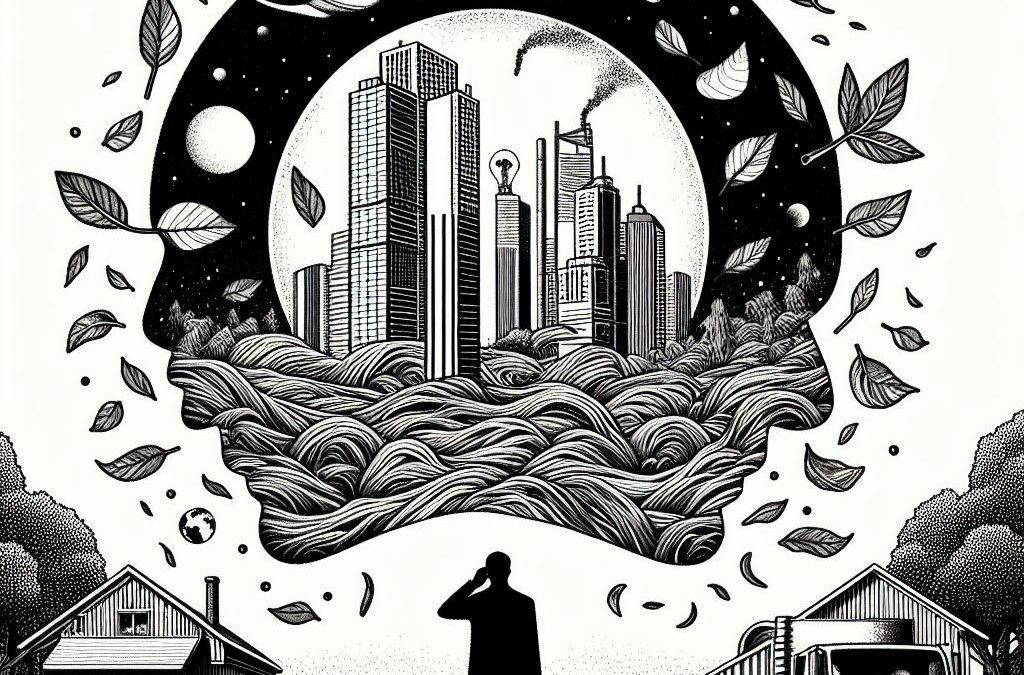

As physiotherapists, we recognize that one of our primary concerns lies in the support of well-being, a concept that is typically viewed through an anthropocentric lens. As underscored by Ton Gevers in his EPA blog post on Actor-network theory, anthropocentrism places humans at the center of well-being, focusing on the physical, mental, and emotional health of individuals. This perspective risks overlooking interconnected relationships of well-being with nonhuman agents and systems, such as those between humans and the environment. In addition to this erasure, we may also encounter narratives of existential threat, which can consign the human position to apathy and disengagement in the face of climate crises and environmental precarity.

In these narratives, we contemplate a ‘natural world’ devoid of human presence, imagining that our finitude- our ending- will be the cure for environmental ills. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, viral headlines announcing a ‘return to nature’ in locked-down cities projected a false optimism around the passive benefits of our reduced presence in the natural environment. Dolphins gamboled in Venice canals; pumas roamed streets in Chile; elephants drank corn wine in China (Jowaheer, 2020; Daly, 2020). Corrado Battisti notes that mass and social media messaging implied a linear cause-and-effect relationship between lockdown measures and reduced human mobility, resulting in a purportedly positive impact on ecosystems (Battisti, 2021). He argues that this simplified and intuitive narrative, as symbolised in the refrain ‘thanks to the Great Pause, Nature recovers,’ ignores the complex socio-ecological phenomenon of the COVID-19 pandemic on a global scale with its cascading effects across multiple temporal and hierarchical levels of ecological impact. He states, ‘It requires critical investigation by researchers … who should try to avoid linear cause–effect relationships and untested optimistic conclusions’ (Battisti, 2021).

In their essay for e-Flux journal, Teresa Castro (2019) demurs from investing too heavily in the appellation of humanity’s passive self-erasure: ‘Extractive capitalism takes its toll everywhere, and environmental breakdown is here to stay. To survive and resist means to adjust, to leave behind reductive stances, and to wrench ourselves loose from our monological, colonizing grip on “nature”. Forests are not stocks of natural resources (even if they’re sustainably explored), nor are they the “lungs of the earth”.’ Eduardo Kohn (2013) in his book How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human, lends credence to this position. His work calls into question fundamental assumptions regarding human exceptionalism and its purported distinction from other forms of life and posits that trees and other organisms possess cognitive abilities, implying that faculties of observation, representation, and even sentience are not exclusive to the human domain. Castro urges us to therefore seek alliances with nature subjects, including forests and other nonhuman constituents of nature, in the process moving to reject dualistic concepts that separate us from nature and more-than-human others (Castro, 2019). One strategy for doing so might be through the ‘queering’ of human self-perception by reframing the subjectivities of the vegetal world. Castro (2019) argues that ‘The “sensitive”, “sentient”, or “intelligent” plant of our current time is necessarily a post-natural mediated plant, a plant interposed by visual and other technologies’: plants are ‘revealed as agentic, intentional beings’ that invite us to ‘develop more caring, attentive, and communicative attitudes toward the vegetal’.

Jessica Laraine Williams (PT, PhD student)

Lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne

As a senior physiotherapist, Jessica has practiced for over a decade in her health profession, including hospital, rehabilitation, and management roles. In 2024, Jessica Laraine is finalising her doctoral research on posthuman subjectivities at the intersection of transdisciplinary research, creativity, and technology.

Image generated with Microsoft CoPilot AI app (GPT 4.5/ DALL.E 3), prompted by Jessica L. Williams 3/2/24. Microsoft Copilot AI-generated images are free to use with copyright protections offered by Microsoft: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2023/09/07/copilot-copyright-commitment-ai-legal-concerns/

Investigating expanded notions of environmental well-being and developments in extended reality technologies, myself and collaborators Ann Borda and Susannah Langley designed the virtual nature artwork Inner Forest in the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The virtual nature experience incorporated multisensory and aesthetic elements based on biophilic design principles (Williams et al, 2021). From our transdisciplinary art-health research, a corollary question emerged:

Could research and dissemination of virtual forest artworks contribute to humanity’s risk of erasing its connection to nature?

This concern aligned with Peter H. Kahn et al.’s concept of ‘environmental amnesia’, cautioning against the potential ‘forgetting’ of actual nature due to immersion in artificial representations (Kahn, et al. 2009, Kahn, 2011).

As physiotherapists, I feel that we can ameliorate these concerns through strategies that engage the human with environmental well-being. We might do this by championing the body-in-relation to nature, as an interconnected and reciprocal node of health that is integral with wider systems of environmental care. Taking on this posthuman conception of well-being thus necessitates the inclusion of a broader spectrum of beings and, consequently, modes and conceptions of nature (including technological, simulated, or designed nature). This expanded perspective allows ‘wellness’ to be more equitably bestowed upon a diverse array of life forms and environments.

I have found that embracing transdisciplinary work offers potential at the boundaries of conventional physiotherapy practice and emerging technologies, enabling approaches that are both critical and creative. This work may intersect with various models of health and well-being, such as OneHealth, ecological/environmental health literacy, climate literacy, environmental consciousness, and pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors.

References

Header image generated with Microsoft CoPilot AI app (GPT 4.5/ DALL.E 3), prompted by Jessica L. Williams 3/2/24. Microsoft Copilot AI-generated images are free to use with copyright protections offered by Microsoft: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2023/09/07/copilot-copyright-commitment-ai-legal-concerns/

Battisti, C. (2021). Not only jackals in the cities and dolphins in the harbours: less optimism and more systems thinking is needed to understand the long-term effects of the COVID-19 lockdown. Biodiversity, 22(3-4), 146-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2021.2004226

Castro, T. (2019). The Mediated Plant. e-flux, (102).

Daly, N. (2020). Fake animal news abounds on social media as coronavirus upends life. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/coronavirus-pandemic-fake-animal-viral-social-media-posts

Gevers, T. (2023, October 12). Have we ever treated patients yet? Actor-network theory and the changing patient in a changing world. Environmental Physiotherapy Association Blog. https://environmentalphysio.com/2023/10/12/have-we-ever-treated-patients-yet-actor-network-theory-and-the-changing-patient-in-a-changing-world/

Jowaheer, R. (2020). 13 photos of animals taking over towns and cities on lockdown. Country Living. https://www.countryliving.com/uk/news/g32066174/animals-deserted-towns-cities-lockdown/

Kahn, P. H. (2011). Technological Nature: Adaptation and the Future of Human Life. Cambridge. The MIT Press.

Kahn, P. H., Severson, R. L., & Ruckert, J. H. (2009). The human relation with nature and technological nature. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 37–42.

Kohn, E. (2013). How forests think: Toward an anthropology beyond the human. University of California Press.

Williams, J. L., Langley, S., & Borda, A. (2021). Virtual nature, inner forest: Prospects for immersive virtual nature art and well-being. Virtual Creativity, 11(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1386/vcr_00046_1