Shaun and Mathieu are physiotherapists with experience in disaster response. They were accepted to present a workshop at the Canadian Physiotherapy Association’s “Congress 2020” on the use of the disaster cycle to conceptualize the roles of physiotherapists in the climate crisis. A summary of that accepted workshop presentation is available here. This blog post develops another of the ideas associated to that workshop.

Note: shortly before posting, Shaun and Mathieu were confirmed as speakers for the October 13, 2020 edition of the CPA’s “Summit Series.”

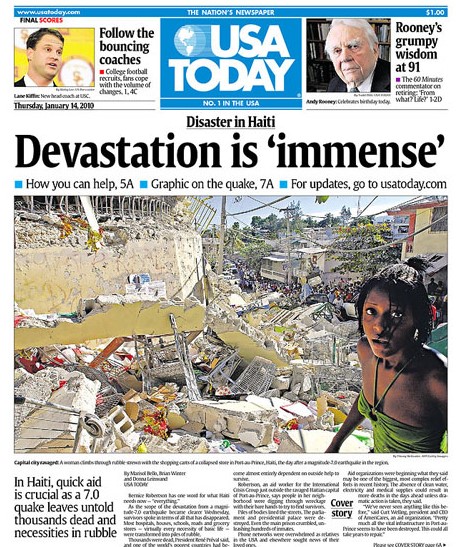

We are physiotherapists who worked in the response to the 2010 Haiti earthquake. When we hear about the earthquake described, the description typically starts out like this:

“A magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti on the afternoon of January 12, 2010…”

Having worked with people who suffered through this event, we have two main thoughts about the typical description:

- A 7.0 earthquake is indeed very powerful

- The earthquake’s magnitude was not the main factor that led to the high toll of death and injury

For those who do not remember the 2010 Haiti earthquake, or never learned much about it in the first place, we will share the following details:

- The earthquake’s epicenter was not far from Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince.

- Although there is uncertainty in the numbers, the estimated deaths are around 100 000, in a country where the estimated population was around 10 000 000.

- There was a significant number of people who experienced spinal cord injuries and had limbs amputated – drawing international attention, including attention from foreign physiotherapists, to support the treatment of these impairments.

Having reviewed these details, we return to the typical description and our main thoughts: the earthquake was powerful and yet the earthquake’s power was not the main factor leading to the suffering.

Haiti’s history is relevant to its situation today. As a physiotherapist who voluntarily offered to travel and work in Haiti in 2004 – shortly after his national government supported a coup d’état of Haiti’s democratically elected president – Shaun made a commitment to learn about Haiti’s history in order to contextualize his own involvement and ensure his own safety in the country. Although a detailed account of Haiti’s history is lengthy and nuanced, a short and straightforward one is still accurate: Haiti became an independent country in 1804 by a slave rebellion. Since that time, it has repeatedly been punished by the “international community.” This series of punishments has exacerbated tensions and inequalities within the country, producing a situation of political and social instability. Public infrastructure and services – including schools, healthcare facilities, drainage systems, and building inspectors – are nearly non-existent. In disaster situations, a lack of infrastructure and services will lead to devastating consequences.

Shaun Cleaver (PhD)

Shaun Cleaver is a physiotherapist and contract academic at McGill University. His research explores disability, rehabilitation, and global health, and has been conducted in partnership with persons with disabilities in Zambia. Shaun’s teaching focuses on professionalism and community health, including service learning and traditional educational formats.

Mathieu Simard

Mathieu Simard is a clinician-professor at the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (UQAC) and doctoral student at McGill University focussing on the nexus of disability and disaster situations for persons with disabilities in Canada and in southern India. Mathieu also chairs RI Rehabilitation International‘s Task Force on Disability, Armed Conflict, and Natural Disasters.

Unsurprisingly, with Haiti’s lack of infrastructure and services, many buildings collapsed in densely populated Port-au-Prince. With few local mechanisms available to help the people trapped inside those collapsed buildings, many people died. With insufficient local health services, there were few options to provide effective treatments to those who did escape; leading to more deaths, questionable amputations, and spinal cord impairments that were more severe than they could have been. Major earthquakes are experienced in many places; in most of those places the powerful earthquakes produce far less suffering.

We draw attention to the 2010 Haiti earthquake because it is well-known, particularly among physiotherapists, and because we had intimate involvement. We also draw attention to it because of the way that it demonstrates how the disaster – the suffering – is more of a result of vulnerable circumstances than it is because of the natural phenomenon. Also, the 200+ years of Haitian history – particularly the way that the country was diplomatically isolated – contributed to the vulnerability.

We all know that earthquakes are not the only “natural” disaster. Extreme storms, fires, floods, heat waves, and cold snaps all team up with vulnerability to produce disasters. More obviously than earthquakes, these other phenomena have increased in frequency and magnitude as part of the climate crisis.

As physiotherapists and as people who wield influence through their political and economic choices, we cannot escape these dynamics: our actions and inactions have impacts on the climate crisis, the extreme weather events, and the responses that happen/do not happen when these weather events become disasters.

In addition to all this, there is one aspect that we think is the most important but ironically the most ignored: that vulnerability that can make a disaster out of an extreme weather event.